Karnaugh Maps#

Simplifying Boolean expressions is not always easy. Algebraic manipulation does not guarantee the final expression is in fact the simplest.

For instance, look at this attempt at simplification through expansion and subsequent factoring.

This is as far as this line of algebric manipulation can go, but can we be sure that the final answer is the simplest expression? In actuality, the most simple form is \(\bar{A}B\bar{D} + \bar{B}C\). You can use a truth table to verify, and if up for a challenge try to see how you can arrive at this expression through Boolean algebra.

When designing circuits, we would like to be sure that we have the simplest circuit possible. Thankfully, there is an algorithm which guarantees the simplest logic expression of 2-4 inputs, known as Karnaugh Mapping. The algorithm can be expanded for situations of more than 4 inputs, but the higher dimensionality quickly makes it impractical to do by hand or even by computer (for large numbers of inputs, heuristic methods are used which will not necessarily provide the optimal simplification, but will quickly approach the optimum).

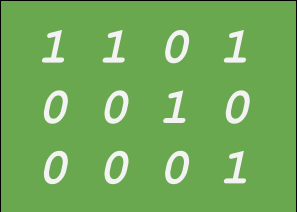

A Karnaugh Map, or K-Map contains the same information as a truth table, but the output is arranged in a 2D grid. It is easiest to start looking at an example. Here is a very simple K-map from a 2-input truth table.

Both possibilities for \(A\) (0 or 1 represented as \(\bar{A}\) and \(A\) respectively) are placed on the vertical axis, and those for \(B\) horizontally.The desired output values for each input combination are then filled in.

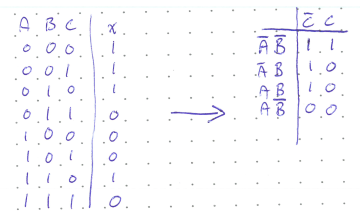

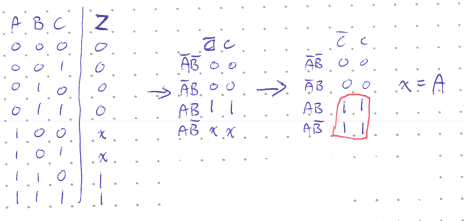

We can construct a K-map from a 3-input truth table by combining the first two inputs on the vertical axis.

Pay particular attention to the order of the vertical axis! It is important that only one variable is inverted at a time (\(\bar{A}\bar{B} \rightarrow \bar{A}B \rightarrow AB \rightarrow A\bar{B}\)). Never have \(\bar{A}\bar{B}\) and AB (or other similar situations with two negations) next to each other.

Looping#

Now, a key concept of K-mapping is the process of looping, where adjacent 1s are grouped together. This is why two negations are never side-by-side. Each row or column is only defined as adjacent to the next if there is exactly one negation.An important note about adjacency: A K-map is actually a cyclical torus, where the top and bottom rows, and left-most and right-most columns are considered adjacent to eachother.

When we make a loop, we are grouping terms that can be simplified algebraically if we were to write out each term in the loop in Sums of Product form. For example, the K-map below has a the output be high when either \(\bar{A}\bar{B}\bar{C}\) or \(\bar{A}B\bar{C}\) is True.

Simplifying this in the usual way gives:

Looping thus allows us to shortcut algebraic simplification. We only keep the inputs that don’t change in a loop (as the others will be factored out and eliminated as above).

Concept Check:

Without doing the algebra, what does this loop simplfy to?

Solution

\(\bar{B}\bar{C}\)

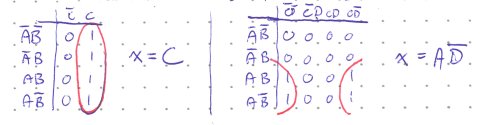

Loops can also come in groups of 4 known as quads,

and in groups of 8 called octets.

Simplification Algorithm#

To guarantee the simplest solution, we want to loop in a way that eliminate the most terms, and not have any redundant loops. The steps to create the minimal expression are

Construct the K-map.

Loop any 1s that are isolated, i.e. not adjacent to any other 1s.

Look any 1s that are adjacent to only one other 1, and loop those pairs.

Loop any octet, even if it contains 1s that have already been looped.

Loop any quads with 1s that remain unlooped, being sure to use the minimum number of loops.

Loop any pairs with 1s that remain unlooped, being sure to use the minimum number of loops.

Form the OR sum of terms generated by each loop.

Example

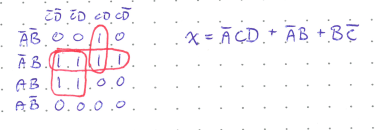

In this example there are no isolated 1s. The 1 in the top row is adjacent to only one other 1 (below it) so we loop that pair first. Then, there are no octets so we look for quads and find two. Once every 1 is looped, we make a term for each loop keeping only the variables that aren’t negated within the loop, and finally OR all those terms together.

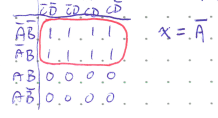

Don’t Care Conditions#

In many circuits there are certain combinations of inputs that will never occur. For example, a 4-bit counter in a digital clock is designed to count to ten and then reset, meaning 1011, 1100, etc. are never encountered. In these cases, we use \(x\) markings in our truth table to show that we don’t care what output the logic circuit gives for these input states, since they never occur. When designing the circuit with a K-map, we can then treat the \(x\)s markings as either 1s or 0s, whichever will simplify things more. In making a simple K-map the main thing to remember is bigger loops are better. In a 4-input K-map, a pair yields an AND term with three variables, while a quad only has two, and an octet only one!

Example

We have the freedom of making each individual don’t-care condition a 0 or a 1 in the K-map. If both are 0s, then we end up with a pair and the circuit \(AB\), if one \(x\) were a 0 and the other 1 we would have something like \(AB + AC\), and if both are 1s we have a quad and the simplest expression of just \(A\).

You don’t have to try out every combination, just find the biggest loops you can.

Exercise:

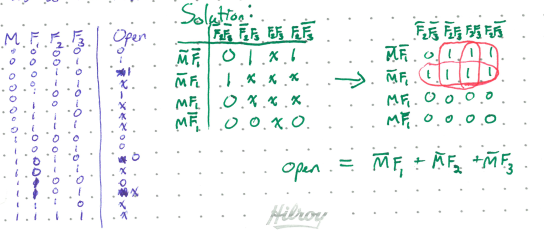

Consider a circuit that controls an elevator door opening. It has for inputs: \(M\) for whether or not the elevator is moving, and \(F_1\), \(F_2\), and \(F_3\) for signifying which floor the elevator is on. Clearly, the elevator cannot be at more than one floor at the same time.

Use a K-map to construct a minimal expression that will be 1 when the doors should open, that is, when the elevator is stopped at a floor.

Solution

With a little forethought, we probably could have come up with this expression on our own without much hassle. But this example illustrates clearly that following the K-map procedure will give the simplest expression.